Originally, the body of this review of Paprika was simply going to be “WTF?” but it turns out I need to write something a bit more substantial. Beware minor spoilers ahead.

Animation offers filmmakers a freedom not found in live-action film-making. In an animated film, animals can dance and sing, furniture can come to life, and a character’s physical performance can be modeled exactly the way a director sees fit. Yes, visual effects technology continues to rocket ahead, but when I’m watching an animated film, I never end up saying “They didn’t quite pull that off,” or “That looks fake.” The audience is submersed in the film’s world from the first frame. If they accept the world and its rules, then chances are they’re going to accept whatever visuals are to follow. The best animation frequently takes advantage of this, telling stories that could not be told as effectively in live-action films. Just look at Pixar’s films – monsters, bugs, toys, cars, fish, and more, all brought to life in a way that captures our imagination without us saying “I think it’s a guy in a costume.”

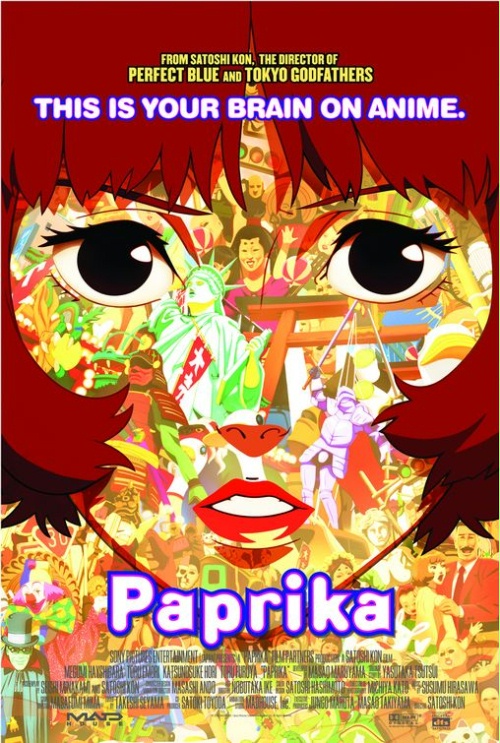

Paprika is a film that showcases animation’s ability to create beautiful, imaginative, and unforgettably weird images in a way a live-action film would have trouble doing. The story centers around the DC Mini, a device which allows the user to enter someone else’s dreams. One Dr. Chiba, part of the research team working on the device, enters dreams as her alter-ego Paprika and interacts with the dreamers as a new form of psychotherapy. When three of the devices are stolen, things spiral out of control quickly, culminating in a violent collision between the dream world and reality.

Paprika’s story is challenging, but I was okay with that. One thing I definitely liked was the lack of an expositional segment to help the audience along. Think back to Inception, a movie about dreams that is almost completely different. There’s a long sequence in which the film’s rules of dreaming (what happens when you die in a dream, who populates a dream, how can you tell if you’re still dreaming, etc.) are explained by one character to another. This gives the audience a basis to understand the actions and motivations in the film. Paprika doesn’t really have this kind of foundation, at least not explicitly. But this is part of what makes the film so interesting to watch. Scenes from the film which take place in the real world are nonetheless filled with images that seem to belong in a dream. As such, you will often find yourself wondering whether what you’re watching is actually reality and not in fact, a dream. The film uses your doubt to great advantage, often plunging into dreams sans warning or transition and pulling you along for the ride. Beyond that, the movie politely refuses to hold your hand.

Paprika herself is also interesting. She reminded me of Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. No, she isn’t a faerie (most of the time) and no, she doesn’t administer love potions, but she is a character of magic who weaves in and out of insane scenarios with ease. She is a product of the freedom of dreams, existing outside the rules of the everyday dreamer (particularly Detective Konakawa). This is true of the other researchers as well, but to less of an extent. For the audience, Paprika is a good friend to have, popping up to confirm that the scene we’re watching is indeed a dream. Paprika’s talent is never clearer than during the film’s climax when she and Dr. Chiba appear to exist as two separate people. Even at this point, the entity Paprika is still a guide of sorts, helping Dr. Chiba through the insanity that has resulted from the collision of dreams and reality.

Some viewers may be put off by Paprika’s emphasis on experience over explanation, but in the end, keeping the audience off-balance in regard to what is real and what isn’t is the only way to make us feel the way its characters feel. And what better way to show dreams than through animation, a medium in which anything you can draw can become the viewer’s reality? Paprika is a beautiful albeit mildly disturbing and complicated film to be watched and re-watched.

RIP Satoshi Kon (1963-2010), director of Paprika.